Plant Doppelgangers: Invasive Plants Often Mistaken for Other Species

Regions across the country are waging war on invasive aquatic plants, with a particular focus on preserving water access and usage. Unless designed for a specific safety purpose, waterbodies are supposed to support aquatic biota, including plants. However, many of these invading species are often mistaken for native plants that are important for a balanced or natural ecosystem. How can pond owners, community associations, and recreational users distinguish between them? What signs help reveal that a plant is ‘invasive’?

Foremost, a large amount of growth in a confined area can be a primary indicator of an unbalanced plant community – often suggesting non-native or invasive growth. Dense growth removes open-water habitat or may decrease the potential species diversity a system can support. Understanding a balance of biota is also key to preserving or restoring an aquatic ecosystem.

Action towards awareness of invaders is also important. Questioning whether or not a species is supposed to be in the waterbody is a great step to take, especially when widespread or ‘new’ growth is present. New plant growth in a lake or pond may indicate the presence of an invasive species, potentially brought in by recreation, urban development or wildlife.

Below are some selected, common nuisance and invasive species that may be confused with species that are desirable and native to the US:

Eurasian Watermilfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum) and Parrotfeather (Myriophyllum aquaticum)

Eurasian watermilfoil and parrotfeather are from the same genus, however, parrotfeather is typically emergent, whereas only the flowering spikes of Eurasian watermilfoil appear above the water’s surface. Both have feather-like leaves arranged in whorls around the stem, with up to six leaves in each whorl. The leaves are comprised of leaflet pairings – creating the feathered appearance – where the count of leaflets can help differentiate species. Parrotfeather leaves tend to appear fleshier than the fine leaves of Eurasian watermilfoil. Typically, they spread through root division, plant fragments, and seed production, however, parrotfeather rarely produces seeds.

Often mistaken for the following native species: Water Marigold (Bidens beckii), Crowfoot (Ranunculus spp.), Bladderwort (Utricularia spp.), Coontail (Ceratophyllum spp.), American Featherfoil (Hottonia inflata), Mermaidweed (Proserpinaca spp.), and Horsetail (Equisetum spp). Fanwort (Cabomba caroliniana) is a nuisance species, considered non-native in northern parts of the country, often mistaken for Eurasian watermilfoil.

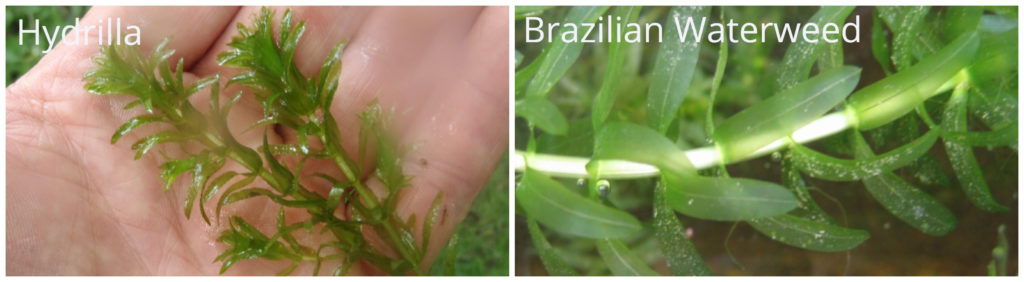

Hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata) and Brazilian Waterweed (Egeria densa)

Brazilian waterweed and hydrilla are similar at a glance, and especially when comparing native look-alike species. Both species have serrated leaves, though Brazilian waterweed has finer teeth that are hard to see without magnification. The leaves appear in whorls along the stem, where Brazilian waterweed leaves have wide, densely-packed 4-6 leaves in a whorl. Hydrilla leaves are thinner and can have between 4-8 leaves in a whorl. Both species produce small white flowers, though hydrilla flowers are smaller and usually submersed. Hydrilla distinctly produces turions (winter buds) in the fall and many tubers along its rhizomes.

Often mistaken for the following native species: common waterweed (Elodea canadensis), western waterweed (Elodea nuttallii), mare’s tail (Hippuris vulgaris), and flatleaf bladderwort (Utricularia intermedia).

Giant Salvinia (Salvinia molesta) and Common Salvinia (Salvinia minima)

Salvinia float on the surface of the water, with fleshy leaves that appear in pairs. A third leaf is emerged and almost root-like in appearance. However, salvinia have no true roots. The surface of the leaves has small bumps, like goosebumps, that also support translucent hairs. The function of the hairs is still unknown. An additional unique characteristic of salvinia is reproduction through spores rather than seeds; salvinia is considered a floating fern, where no seeds or flowers are formed for reproduction.

Often mistaken for the following native species: duckweed (Lemna spp. and Spirodela polyrhiza) and mosquito fern (Azolla spp.), however, some mosquito fern species are considered non-native in some areas of the US. Water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) and water lettuce (Pistia stratiotes) are two non-native species that are commonly mistaken for salvinia species. While often found in nuisance quantities, both species are used as beneficial habitat for juvenile fish.

Yellow Floating Heart (Nymphoides peltata) and European Frog-bit (Hydrocharis morsus-ranae)

Both of these species have small heart-shaped floating leaves that can aggressively cover the water’s surface with dense growth. Yellow floating heart is characterized by its bright yellow flower and purple underside of its leaves. Unlike native floating heart species, multiple floating leaves can growth per rooted stem. European frog-bit looks extremely similar to native floating heart species, with a small white flower and unbranched stems. However, European frog-bit is distinctly free-floating, much like water hyacinth or salvinia, and has a slightly larger flower with only three petals and a showy yellow center. Yellow floating heart is a more widespread non-native and can spread by seeds, fragmentation, and rhizomes. If a leaf and stem become detached from the parent plant, a new plant can form. European frog-bit is a ‘newer’ invasive species to the US and is confined to small populations. Reproduction is primarily achieved through turions and stolon (root-like structure) regrowth.

Often mistaken for the following native species: little floating heart (Nymphoides cordata), white waterlily (Nymphaea odorata), yellow waterlily (Nuphar spp.), and watershield (Brasenia schreberi)

Curly-leaf Pondweed (Potamogeton crispus) and Brittle Naiad (Najas minor)

While sharing many characteristics with native pondweeds, curly-leaf pondweed’s primary distinguishing features are its leaves. Finely serrated, the leaves are curvy along the edge, causing the appearance of a lasagna noodle or crimped hair. In addition to an immersed flowering stalk, curly-leaf pondweed forms a unique turion that promotes annual growth; the turion breaks off the parent plant, sinks to the pond bottom and can grow a new plant immediately if conditions are optimal. Since curly-leaf pondweed is adapted to cooler water conditions, it is less common to see growth in warmer weather, regionally. Brittle Naiad has stiff, toothed leaves in whorls along a branched stem, where only 3-4 leaves are present in each whorl. Often mistaken for other native naiads, the seeds are the only true way to differentiate between the various species since the vegetative structures can be visually similar. The fan-shaped base of the leaf, can also help distinguish brittle naiad from other native naiad species.

Often mistaken for the following native species: Other naiads (N. marina, N. flexilis, N. guadalupensis, N. gracillima), water starworts (Callitriche spp.), thin-leaf pondweeds (Potamogeton spirillus, P. pusillus, P. berchtoldii, P. gemmiparus), and macro-alga (Nitella spp. and Chara spp.), ribbon-leaf pondweed (P. epihydrus), alpine pondweed (P. alpinus), large-leaf pondweed (P. amplifolius), clasping-leaf pondweed (P. perfoliatus), Richardson’s pondweed (P. richardsonii), and white-stem pondweed (P. praelongus).

It can be hard to tell plants apart, which is why it’s important to consult with an aquatic biologist if you ever spot a new plant growing in or around your waterbody. Using lab tests, specialized equipment and years of expertise, they can accurately determine the identification of the species and make appropriate recommendations for the long-term management of the aquatic plant. Recognize any of the plants above? Contact your lake management professional.

Aquatic Weed & Algae Control

SOLitude Lake Management is a nationwide environmental firm committed to providing sustainable solutions that improve water quality, enhance beauty, preserve natural resources and reduce our environmental footprint. SOLitude’s team of aquatic resource management professionals specializes in the development and execution of customized lake, stormwater pond, wetland and fisheries management programs that include water quality testing and restoration, nutrient remediation, algae and aquatic weed control, installation and maintenance of fountains and aeration systems, bathymetry, shoreline erosion restoration, mechanical harvesting and hydro-raking, lake vegetation studies, biological assessments, habitat evaluations, and invasive species management. Services and educational resources are available to clients nationwide, including homeowners associations, multi-family and apartment communities, golf courses, commercial developments, ranches, private landowners, reservoirs, recreational and public lakes, municipalities, drinking water authorities, parks, and state and federal agencies. SOLitude Lake Management is a proud member of the Rentokil Steritech family of companies in North America.